BREAKING! U.S.NIH Study Warns Of Potetial Human Outbreak Of A New Primate Hemorrhagic Fever-Causing Arterivirus From Africa That Is Far Worse Than HIV!

Source: Medical News - Simian arteriviruses Oct 05, 2022 3 years, 2 months, 4 weeks, 1 day ago

A new U.S. NIH sponsored study has shockingly found that a primate hemorrhagic fever-causing arterivirus from Africa has acquired the necessary mutations to cross over into the human species using the CD162 receptors for cellular entry.

It should be noted that the African continent is a hub for various emerging pathogens and diseases and in fact, one theory that has not been properly explored is that even the SARS-CoV-2 virus actually originated from the African continent and was ‘exported’ to China via the illegal wildlife trade and was also spreading in Europe via human vectors. HIV, Ebola, Monkeypox and a number of other infectious and lethal diseases all originated form the African continent. While some are claiming that it is politically incorrect to label the African continent as being the origins of all these diseases, the fact remains and with an African national heading the WHO, we can expect bias health policies and strategies dealing with emerging pandemic threats. In reality, many countries should start banning travel to and fro the African continent and also start strong vigilance of all imports from the continent. Governments and health authorities have yet to learn their lessons from the HIV, Monkeypox and Omicron spread!

The new study of the potential threat of the new primate hemorrhagic fever-causing arterivirus from Africa with parallels to HIV was conducted by researchers from the Ohio State University, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, University of Colorado, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, North Carolina State University and the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

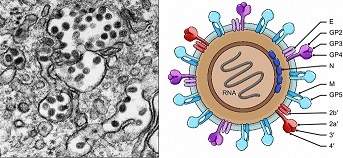

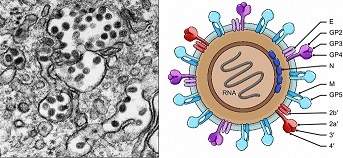

It is already known that most

Simian arteriviruses are endemic in some African primates and can cause fatal hemorrhagic fevers when they cross into primate hosts of new species.

The study team found that CD163 acts as an intracellular receptor for simian hemorrhagic fever virus (SHFV; a simian arterivirus), a rare mode of virus entry that is shared with other hemorrhagic fever-causing viruses (e.g., Ebola and Lassa viruses).

It was also found that the SHFV enters and replicates in human monocytes, indicating full functionality of all of the human cellular proteins required for viral replication.

Hence the simian arteriviruses in nature have already evolved with the relevant mutations and may not require major adaptations to the human host.

Given that at least three distinct simian arteriviruses have caused fatal infections in captive macaques after host-switching, and that humans are immunologically naive to this family of viruses, development of serology tests for human surveillance should be a priority.

The study findings were published in the peer reviewed journal: Cell.

https://www.cell.com/cell/fulltext/S0092-8674(22)01194-1

The key findings of the study are:

-SHFV uses an intracellular receptor, CD163, for cellular entry

-CD163 divergence in primates of some species poses a barrier to SHFV entry

-All cellular proteins required for SHFV replication are functional in huma

n cells

-SHFV replication in human cells suggests potential for zoonotic transmission

The study team using parallels to HIV, are calling on the global health community to be vigilant and to be prepared as the obscure family of viruses, already endemic in wild African primates and known to cause fatal Ebola-like symptoms in some monkeys, is “poised for spillover” to humans.

Though such arteriviruses are already considered a critical threat to macaque monkeys, no human infections have been reported thus far. In addition, it is uncertain what impact the virus would have on humans should it jump species.

The study team evoking parallels to HIV (the precursor of which originated in African monkeys), are calling for vigilance nevertheless.

Co-corresponding author Dr Jens H. Kuhn Jens H. Kuhn from the Integrated Research Facility at Fort Detrick, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases-Maryland told Thailand

Medical News, “By watching for arteriviruses now, in both animals and humans, the global health community could potentially avoid another pandemic.”

Senior author Dr Sara Sawyer, a professor of molecular, cellular and developmental biology at Colorado University, Boulder added, “This animal virus has figured out how to gain access to human cells, multiply itself, and escape some of the important immune mechanisms we would expect to protect us from an animal virus. That’s pretty rare. We should be paying attention to it.”

At present, there are thousands of unique viruses circulating among animals around the globe, and most of them cause no symptoms in the host. Increasing numbers of these viruses have jumped to humans in recent decades, wreaking havoc on naïve immune systems with no experience fighting them off. This includes Middle Eastern Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) in 2012, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) in 2003, and SARS-CoV-2 (the virus that causes COVID-19) in 2020.

Dr Sawyer’s lab for more than 15 years has used laboratory techniques and tissue samples from wildlife from around the globe to investigate which animal viruses may be prone to jump to humans.

In their latest study, she and first author Dr Cody Warren, a postdoctoral fellow at the BioFrontiers Institute at Colorado University, zeroed in on arteriviruses. These are common among pigs and horses but understudied among nonhuman primates.

Specifically, the study team looked at simian hemorrhagic fever virus (SHFV), which causes a lethal disease similar to the Ebola virus disease. Dating back to the 1960s, it has been causing deadly outbreaks in captive macaque colonies.

The study findings showed that a molecule, or receptor, called CD163, is crucial to the biology of simian arteriviruses, enabling the virus to invade and cause infection of target cells.

Using a series of laboratory experiments, the study team discovered, much to their surprise, that the virus was also remarkably skilled at latching on to the human version of CD163, getting inside human cells, and quickly making copies of itself.

Alarmingly, similar to the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and its precursor simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV), simian arteriviruses also appear to attack immune cells. This means they can disable key defense mechanisms and take hold in the body long-term.

Dr Warren added, “The similarities are profound between this virus and the simian viruses that gave rise to the HIV pandemic.”

The study team suggest that the global health community prioritize the further study of simian arteriviruses and develop blood antibody tests for them. They should also consider surveillance of human populations with close contact with animal carriers.

Already an expansive variety of African monkeys already carry high viral loads of diverse arteriviruses, often without symptoms. Additionally, some species frequently interact with humans and are known to bite and scratch people.

Dr Warren added, “Just because we haven’t diagnosed a human arterivirus infection yet doesn’t mean that no human has been exposed. We haven’t been looking.”

The study team noted that in the 1970s, no one had heard of HIV either.

It is now widely known now that HIV likely originated from SIVs infecting nonhuman primates in Africa, likely jumping to humans sometime in the early 1900s.

Originally, when it began killing young men in the United States in the 1980s, no serology test existed, and no treatments were in the works.

The study team warns that although there is no guarantee that these simian arteriviruses will jump to humans, one thing is for sure is that more viruses will jump to humans, and they will cause disease.

Dr Sawyer added, “COVID is just the latest in a long string of spillover events from animals to humans, some of which have erupted into global catastrophes. Our hope is that by raising awareness of the viruses that we should be looking out for, we can get ahead of this so that if human infections begin to occur, we’re on it quickly.’

Currently there is no word about the threat of such simian arteriviruses from the WHO.

For more on

Simian Arteriviruses, keep on logging to Thailand

Medical News.