China Pioneering CRISPR Gene-Editing Technology To Treat HIV And Other Diseases

Source: Thailand Medical News Sep 22, 2019 6 years, 2 months, 4 weeks, 13 hours, 31 minutes ago

With lesser regulatory controls and a more conducive environment for research, China is stepping ahead of the gene-editing game and is now doing extensive research and trials in using the CRISPR Gene-editing platform to find possible cures for a variety of diseases and ailments including a recent trial in which gene-editing was applied to try to cure a patient who had HIV and also leukemia. Though the trial was only partially successful, it marked a very important beginning and step that could lead to potential cures for HIV using the CRISPR platform.

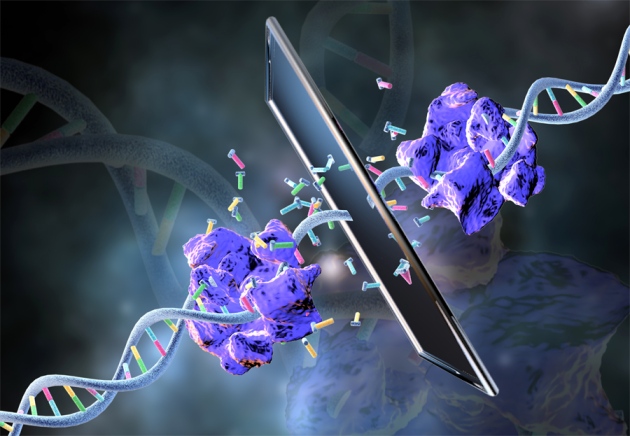

Regarded as a revolutionary leap forward for conducting research and finding potential treatments for disease, CRISPR makes it quicker and easier to edit DNA. The technique called CRISPR-Cas9 involves using the Cas-9 protein to snip at a specific part of DNA.

Crispr has been compared to a word-processing system that allows writers to easily cut out extraneous words and correct typos. With DNA, it acts like molecular scissors, precisely trimming specific flaws in genes. Scientists are still trying to determine if tinkering with the genome can create stray errors elsewhere or lead to unexpected harms, such as cancers caused by uncontrolled cell growth

USING CRISPR AND GENE-EDITING TO CURE HIV

The Chinese Researchers from Peking University Stem Cell Research Center in Beijing used CRISPR to edit a donor's stem cells and transplant them into a 27-year-old patient with HIV and leukemia. They anticipated that the cells would survive, replicate, and cure the man of HIV.

The approach involved knocking out the CCR5 gene in the donor's stem cells. CCR5 encodes a protein that HIV uses to get inside human blood cells, and past research has shown those with a mutation on the gene are protected from HIV.

The team was able to edit 17.8 percent of a donor's stem cells, and the gene-edited cells were still working 19 months after they were transplanted.

However, they made up five to eight percent of the recipient's stem cells. Just over half of the edited cells had died away.

The team was pleased to find the man didn't appear to suffer any adverse effects linked to the transplant.

The patient is in good

health, his cancer in full remission.The edited stem cells survived and are still keeping his body supplied with all the necessary blood and immune cells, and a small percentage of them continue to carry the protective CCR5 mutation. Not enough to have cured him of HIV, but he remains infected and on antiretroviral drugs to keep the virus in check. Still, experts say the new case study shows this use of Crispr appears to be safe in humans and moves the field one step closer toward creating drug-free HIV treatments.

The findings were published in the New England Journal Of Medicine.

Dr Hongkui Deng, a biologist at Peking University in Beijing who led the study,

told Thailand Medical News he was also one of the researchers that identified the role CCR5 plays in HIV infection in 1996.

"I

t was quite exciting that it was me to complete the cycle. This was the first trial, so the most important thing was to test safety. Our results show the proof of principle and we hope the approach could also be used to treat other diseases as well” he said.

Professor of immunotherapy at the University of Pennsylvania, Dr Carl June, wrote an editorial in the New England Journal Of Medicine commenting on the the work. "They need to approach 90 percent or more, I think, to actually have a chance of curing HIV. It was positive attempt on the part of the researchers however.”

Dr Fyodor Urnov,a biomedical scientists at the University of California, Berkeley who did not work on the study commented "This is an important step towards using gene editing to treat human disease. I'm not surprised that five percent was not enough to lower the viral load, but now we know that CRISPR-edited cells can persist, and that we need to do better than five percent. Because of this study, we now know that these edited cells can survive in a patient, and they will stay there. The approach appeared to be safe and precise, and it raised no ethical concerns.”

However many in the

medical and research community were commenting as to how quickly the team went from a proof of concept in animals to a trial in a human in two years. Such a process would take five years in the U.S. This may be an indication that the regulatory environment in China permits more rapid translation than that in the U.S.

HIV and AIDS has been at the vanguard of cell and gene therapy for decades, and this trend has continued in genome editing.

CHINA LEADING THE RACE IN CRISPR AND GENE-EDITING

Researchers are now planning to try to increase the number of cells that are transformed and can thrive inside of a patient. Other diseases with genetic causes, such as sickle cell anemia, muscular dystrophy, cystic fibrosis and cancer are likely to see a surge in interest based on the new results.

While the NEJM report is the first publication about the use of Crispr in humans, other pioneering researchers have been using it for years in China.

The first trials started in 2016, when Dr Lu You, a physician at Sichuan University, put gene-edited cells into a lung-cancer patient. Since then, scientists have launched multiple trials and reportedly treated dozens of patients. But little is known about some of those studies, and

medical research is not as stringently regulated in China as it is in the West, prompting concerns about their safety and ethics.

However, in the next 18 to 24 months, we’ll start to see published results from a number of these ongoing trials in China. The Chinese government is also supporting the

medical genomics and gene-editing platforms by investing millions of dollars into both public and private research laboratories and facilities and encouraging more works into these fields. It is already known fact that China has already even surpassed the US and Europe in terms of advances in the field of CRISPR and gene-editing.