Sourec: Thailand Medical News Nov 01, 2019 5 years, 11 months, 2 weeks, 1 day, 21 hours, 28 minutes ago

Researchers from Johns Hopkins Medicine have identified three so-called “complement system” genes that appear to play a role in debilitating forms of

multiple sclerosis (

MS) conditions including

MS-caused vision loss. The researchers were able to single out these genes known to be integral in the development of the brain and immune systems by using DNA from

MS patients along with high-tech retinal scanning.

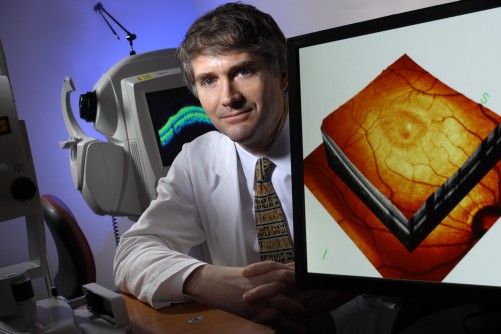

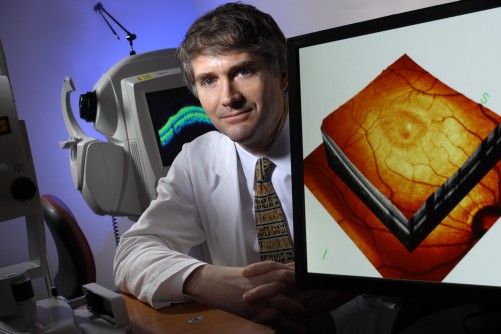

Dr. Peter Calabresi (credit: John Hopkins Medicine)

Dr. Peter Calabresi (credit: John Hopkins Medicine)

The investigators say these could serve as markers for monitoring and predicting progression and severity of

MS, an unpredictable disorder in which the immune system eats away at protective insulation around nerve cells. This approach, the researchers say, represents the beginning of precision medicine for

MS and may ultimately allow designer therapies, as is being done for specific cancers.

In M

ultiple Sclerosis, nerve communication breaks down over time between the brain and the rest of the body, causing chronic and/or intermittent muscle spasms, tremors, imbalance, pain, numbness, depression, loss of bladder or bowel control and vision problems.

MS is more common in women, and symptoms vary widely.

According to the National

Multiple Sclerosis Society, nearly one million people in the U.S. have

MS, and there is no permanent cure for the condition. Globally about 26 million people are stricken with MS.

Dr Peter Calabresi, M.D., professor of neurology and neuroscience at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and co-director of the Johns Hopkins Precision Medicine Center of Excellence for Multiple Sclerosis told

Thailand Medical News, “Although we have treatments for the type of

MS where symptoms come on in bursts called relapsing-remitting

MS, we don’t have any way to stop the kind of

MS in which the nerve cells start to die, known as progressive

MS. We believe that our study opens up a new line of investigation targeting complement genes as a potential way to treat disease progression and nerve cell death.”

/>

The researchers used optical coherence tomography, an imaging technique that allowed the researchers to look at the back of each patient’s eyes and assess damage to the nerve cells in the retina in 374 patients with all types of MS. The patients were an average of 43 years old and mostly women (78%).

The researchers recruited these patients and performed imaging every few years from 2010 to 2017, yielding an average of 4.6 scans per participant over the course of the study. The scans were used to measure thinning of the layer of the nerve cells, known as ganglion cells in the retina over time. The average rate of deterioration was a loss of 0.32 micrometers of tissue per year in each patient.

Using blood samples from the patients to collect their DNA, the researchers hunted for genetic mutations in those people with the fastest deterioration rates and identified 23 such DNA variations that mapped to the complement gene C3.

To search for genes further linked to vision loss, they performed an analysis of an existing clinical trial group of another 835 people with MS, of whom 74% were women, and whose average age was 40. Each participant underwent periodic vision testing about every year to distinguish their ability to detect contrast finer and finer shades that distinguish light versus dark. The test requires the person to read five letters in a row as with a typical vision chart test, as well as separate vison charts with faint (low contrast) letters that simulate vision in low light (dusk or dark).

Utilizing DNA from the blood samples of these 835 participants, the researchers identified specific genetic changes in two complement genes, C1QA and CR1, linked to those people with the most rapidly declining ability to distinguish letters with less contrast. Patients with genetic changes in the C1QA gene were 71% more likely to develop difficulty detecting visual contrast, whereas those with genetic changes in the CR1 gene were at 40% increased risk for developing a reduced ability to detect contrast. These complement genes found to be linked with severity of Multiple Sclerosis vision loss hold the genetic instructions for making complement proteins.

Dr Peter Calabresi told Thailand Medical News “Complement proteins have traditionally been thought of as part of the immune system, binding to antibodies and helping them kill infected cells in the body. A decade ago, however, other researchers discovered that complement proteins bind to the connections between neurons and helps them grow in specific directions. But, too much complement was found to causes damage to the nerve cells, eventually killing them. Our findings fit well into this system.”

Dr Kathryn Fitzgerald, Sc.D., assistant professor of neurology at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and first author of the published report commented to Thailand Medical News, “Our next step will be to repeat these studies in larger populations. Next, animal studies looking further into the function of complement proteins will also need to be performed so we can figure out the mechanism behind their role in killing nerve cells in people with Multiple Sclerosis. From there we can possibly think about how to design new therapies.”

Reference: Early complement genes are associated with visual system degeneration in multiple sclerosis Kathryn C Fitzgerald, Kicheol Kim, Matthew D Smith, Sean A Aston, Nicholas Fioravante, Alissa M Rothman, Stephen Krieger, Stacey S Cofield, Dorlan J Kimbrough, Pavan Bhargava Brain, Volume 142, Issue 9, September 2019, Pages 2722–2736, https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awz188