Source: University Of California, Santa Barbara Mar 31, 2019 6 years, 3 weeks, 5 days, 14 hours, 56 minutes ago

Dementia — an umbrella term for various neurodegenerative conditions involving memory loss and other forms of cognitive impairment — is hard to treat because its causes remain unknown. Researchers, however, are making painstaking progress.

Dr. Kenneth Kosik, the Harriman Professor of Neuroscience at the University of California (UC), Santa Barbara recently led a team of experts who were focusing on using a known drug to treat the toxic buildup of a protein called "tau" in the brain.

Usually, tau proteins play a role in stabilizing microtubules. These are elements of axons, the "stems" that link neurons (brain cells) together and allow them to communicate.

However, perhaps as a result of a mutation, tau proteins sometimes misfold, which means that they become sticky and poorly soluble, "clogging up" the connections between brain cells.

These changes are consistent with the development of a form of dementia called "frontotemporal dementia," which affects the temporal and frontal lobes of the brain, resulting in impaired emotional expression, behavior, and decision-making abilities.

"Patients do not initially show very many, if any, memory problems in this condition. They tend to show more psychiatric problems, often with impulsive personalities in which they show inappropriate behaviors," siad Dr. Kosik in an

interview with Thailand Medical News.

In the current study, Dr. Kosik's team collected samples of skin cells from individuals who had mutated forms of tau. Then, in the laboratory, the scientists converted these sampled cells into stem cells and then into neurons so that they could trace what kinds of genetic mutation might affect tau.

The findings, which the researchers report in the journal

Science Translational Medicine, indicated that three genes presented dysregulations in tau mutations.

Of these three genes, however, the team focused on one ,

RASD2 which drives the activity of energy-producing molecules called GTPases.

"People had already talked about this gene as possibly involved in Huntington’s disease, which is another neurodegenerative disease," explains Dr. Kosik, adding that

RASD2 and another similar gene called

RAS have attracted a lot of attention from researchers because they appear to be responsive to drugs.

"There are drugs or potential drugs or small molecules that are out there that could affect the levels of this gene," Dr. Kosik notes.

While studying

RASD2, the researchers were intrigued by a GTPase called RHES, which this gene encodes. However, while RHES's activity as a protein is the usual focus of studies, the team were interested in other aspects of this GTPase.

"What we ended up focusing on was the fact that this protein and all members of its family are attached to the cell membrane in a very interesting way," says Dr. Kosik.

;

RHES, he explains, attaches to the inside of cell membranes through a carbon chain known as a "farnesyl group." Scientists refer to the attachment process as "farnesylation."

"There's an enzyme called farnesyl transferase that takes this protein, RHES, and attaches it to the membrane, and we decided to focus on that reaction," says Dr. Kosik, admitting that "[i]t was a bit of a jump to go in the direction."

Past research on farnesyl transferase has focused on disrupting farnesylation, hypothesizing that this action could help treat cancer tumors. In fact, "it turns out the drugs in this category, called farnesyltransferase inhibitors, have been tested in humans," Dr. Kosik points out.

He notes that these drugs are "safe," though "they did not work in cancer." Could the farnesyltransferase inhibitors work as a dementia treatment though? That is what the UC Santa Barbara researchers set out to determine.

They tested a drug that had failed as a cancer treatment , Lonafarnib in mouse models of dementia, and this attempt was promising. The mice that presented erratic behaviors at 10 weeks were behaving normally at 20 weeks.

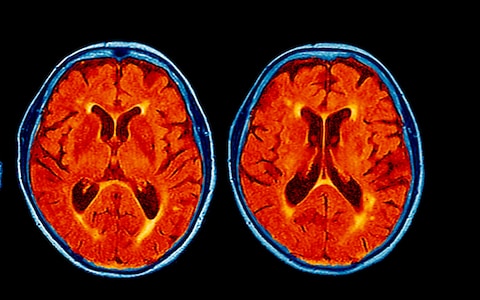

When they scanned the rodents' brains, the scientists found that the drug had halted inflammation and tissue damage in the brain. It had also greatly reduced the number of tau tangles, these sticky buildups were, in fact, all but gone in the hippocampus, the region of the brain that plays the most significant role in memory recall.

"The drug is very interesting. It seems to have a selective effect on only the forms of tau that are predisposed to forming the neurofibrillary tangles," Dr. Kosik observes.

To ensure that Lonafarnib acted by attacking farnesylated RHES, the researchers looked at another set of mouse models of dementia in which they activated a gene that blocks RHES production.

In this case, the behavior of the mice improved in the same way as it had with Lonafarnib treatment, which proves that the drug's action on farnesylated RHES is responsible for its benefits.

"This makes us begin to think that although indeed the drug is a general farnesyl transferase inhibitor, one way it's actually working is by specifically targeting the farnesylation of RHES. And, fortunately, the other farnesyl inhibitions that it's also doing are not toxic." Dr. Kenneth Kosik.

Now, the UC Santa Barbara scientists are interested in taking their research to the next step and are looking at organizing the first clinical trials with human volunteers.

The first step from here, the team explains, would be to ensure that the drug can penetrate the human brain and reach its target: farnesylated RHES in neurons.

However, the researchers are already facing a major obstacle because the makers of Lonafarnib are currently testing the drug for another indication, namely as a treatment for a genetic disorder called progeria.

Thus, Lonafarnib is off-limits until this trial's results come in and the drug receives its approval. "It's a big challenge," Dr. Kosik admits.