Source: Thailand Medical News Dec 12, 2019 5 years, 4 months, 2 weeks, 18 hours, 9 minutes ago

Medical researchers from Australia and the US have discovered and identified the genetic cause of a previously unknown human

autoinflammatory disease. The scientific team determined that the

autoinflammatory disease, which they termed

CRIA (

cleavage-resistant RIPK1-induced autoinflammatory)

syndrome, is caused by a mutation in a critical cell death component called

RIPK1.

The study team was led by Dr. Najoua Lalaoui and Professor John Silke from the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research, Australia, and Dr. Steven Boyden, Dr. Hirotsugu Oda and Dr. Dan Kastner from the National Human Genome Research Institute at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), US. The study was published in

Nature.

CRIA Syndrome

CRIA Syndrome

Dr Lalaoui told

Thailand Medical News, "Cell death pathways have developed a series of inbuilt mechanisms that regulate inflammatory signals and cell death, because the alternative is so potentially hazardous. However in this disease, the mutation in

RIPK1 is overcoming all the normal checks and balances that exist, resulting in uncontrolled cell death and inflammation."

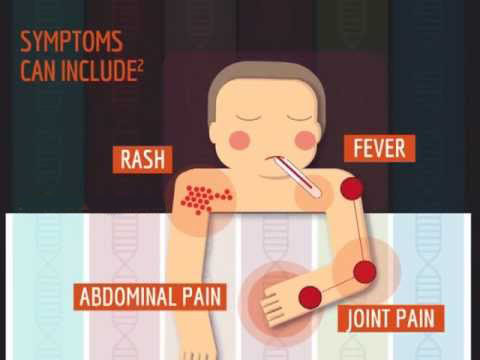

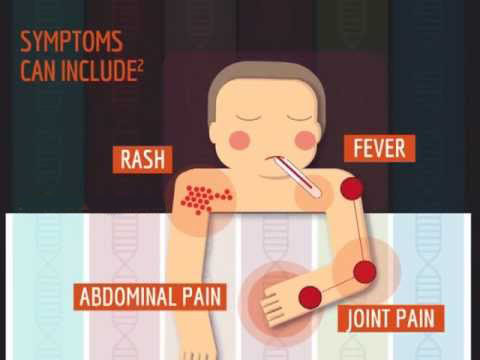

Typically,

autoinflammatory diseases are caused by abnormal activation of the innate immune system, leading to recurrent episodes of fever and inflammation that can damage vital organs. In the paper, the researchers describe patients from three families with a history of episodic high fevers and painful swollen lymph nodes. The patients, who were diagnosed with a new

autoinflammatory disease (

CRIA syndrome), had a host of other inflammatory symptoms which began in childhood and continued into their adult years.

Dr Steven Boyden from NIH said the first clue that the disease was linked to cell death was when they delved into the patients' exomes, the part of the genome that encodes all of the proteins in the body. "The team sequenced the entire exome of each patient and discovered unique mutations in the exact same amino acid of

RIPK1 in each of the three families," Dr. Boyden said. "It is remarkable, like lightning striking three times in the same place. Each of the three mutations has the same result ie it blocks cleavage of

RIPK1 which shows how important

RIPK1 cleavage is in maintaining the normal function of the cell."

Walter and Eliza Hall Institute researchers had confirmed the link between the

RIPK1 mutations and

CRIA syndrome in laboratory models. "We showed that mice with mutations in the same location in

RIPK1 as in the

CRIA syndrome patients had a similar exacerbation of inflammation," she said.

Widely regarded as the 'father of

autoinflammatory disease', Dr. Dan Kastner said the NIH team had treated

CRIA syndrome patients with a number of

anti-inflammatory medicati

ons, including high doses of corticosteroids and biologics. Although some of the patients markedly improved on an interleukin-6 inhibitor, others responded less well or had significant side effects.

Dr Kastner added, "Understanding the molecular mechanism by which

CRIA syndrome causes inflammation affords an opportunity to get right to the root of the problem.”

He noted that

RIPK1 inhibitors which are already available on a research basis may provide a focused, 'precision medicine' approach to treating patients.

Dr Kastner further commented, "

RIPK1 inhibitors may be just what the doctor ordered for these patients. The discovery of

CRIA syndrome also suggests a possible role for

RIPK1 in a broad spectrum of human illnesses, such as colitis, arthritis and psoriasis."

Research laboratories at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute are devoted to disentangling the complicated pathways associated with cell death. Cell death research began at the Institute in the 1980s, with the discovery that mutations in the Bcl-2 protein could keep cancer cells alive.

Professor John Silke has been studying cell death pathways for more than 20 years, and said

RIPK1 was a critical regulator of inflammation and cell death. "

RIPK1 is a potent molecule," Professor Silke said. "The cell has developed a way of managing its effects, which includes cleaving

RIPK1 into two pieces to 'disarm' the molecule and halt its inflammatory activity. In this

autoinflammatory disease, the mutations are preventing the molecule from being cleaved into two pieces, resulting in uncontrolled cell death and inflammation."

RIPK1 was a complex protein, with a complicated role in cell death pathways.

Professor Silke added, "Mutations in

RIPK1 can drive both too much inflammation such as in

autoinflammatory and autoimmune diseases and too little

inflammation, resulting in immunodeficiency. There is still a lot to learn about the varied roles of

RIPK1 in cell death, and how we can effectively target

RIPK1 to treat disease."

Reference: Mutations that prevent caspase cleavage of RIPK1 cause autoinflammatory disease, Nature (2019). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-019-1828-5 , https://nature.com/articles/s41586-019-1828-5