Source: Tuff University Dec 04, 2018 6 years, 4 months, 3 weeks, 2 days, 23 minutes ago

A research team led by Tufts University engineers has developed a non-invasive method for detecting bladder cancer that might make screening easier and more accurate than current invasive clinical tests involving visual inspection of bladder. In the first successful use of atomic force microscopy (AFM) for clinical diagnostic purposes, the researchers have been able to identify signature features of cancerous cells found in patients' urine by developing a nanoscale resolution map of the cells' surface, as reported today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

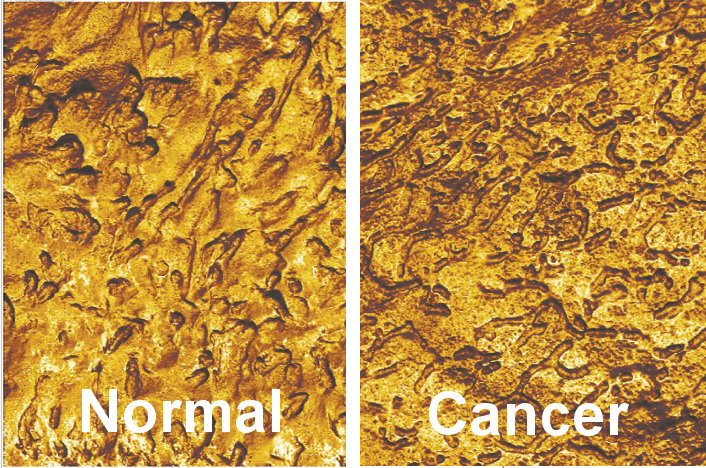

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) map of the adhesion features of the cell surface for a normal cell (left) versus a cancer cell (right) isolated from the urine of patients. Credit: Igor Sokolov, Tufts University

Bladder

cancer is one of the leading causes of cancer-related deaths in the United States, with the American Society of Clinical Oncologists estimating 17,240 deaths for 2018. While early detection leads to a five-year survival rate of 95 percent ,bladder cancer detected at the metastatic stage leaves the patient with only a 10 percent chance of survival after five years. Current methods for detection involve cystoscopy (running a tube with a video camera into the bladder through the urethra), as well as possible biopsy, and pathology examination of the tissue sample. For patients who have been treated and are in remission, the recurrence rate is high—between 50 and 80 percent, so invasive cystoscopy exams must be conducted every three to six months at great expense and discomfort for patients.

"By introducing a non-invasive diagnostic method that is more accurate than the invasive visual examination, we could significantly decrease the cost and inconvenience to patients," said Igor Sokolov, professor of mechanical engineering and biomedical engineering at Tufts University School of Engineering and lead author of the study. "All that is needed is a urine sample, and not only could we more effectively monitor patients after treatment, we could also more easily screen healthy individuals who may have a family history of the disease, and potentially detect the grade of cancer development. Determining the efficiency of early screening and grade detection is a separate, important task of our future research. "

AFM involves scanning over a surface with a very small cantilever, which is deflected from its position as it passes over the bumps and valleys on the surface. Recording the deflections allows a topographical map to be created with a resolution of fractions of a nanometer. Moreover, the deflection of the AFM cantilever is indicative of some physical properties of the sample. For example, one can measure the adhesion force between the AFM probe and the sample surface. The researchers discovered that bladder cells extracted from urine of a cancer patient have unique surface features that distinguish them from cells extracted from a healthy person, allowing the researchers to apply the method as a diagnostic tool.

The diagnostic method incorporates machine learning, enabling a more accurate recognition of the signature surface features, such as adh

esion, roughness, directionality, and fractal properties, among others. The AFM-based test demonstrates more than 90 percent sensitivity in detecting bladder cancer (i.e. if a person is known to have the disease, the test will detect it 90% of the time) versus 20 to 80 percent sensitivity for currently available non-invasive diagnostics on urine samples, such as biochemical evaluation of the biomarker NMP22, genetic analysis using fluorescence in situ hybridization, or immunocytochemistry. Specificity of AFM—the accuracy of identifying individuals who do NOT have the disease—is 82-98%, which is comparable to other tests.

"AFM has been around for more than 30 years, but this is the first time it has shown promise for clinical diagnostics," said Sokolov. "The accuracy appears to be better than the current clinical standard for bladder cancer diagnosis, but we will need to test the method on a larger cohort of patients before it can be introduced into clinical practice. We are hopeful that AFM could ultimately be applied to the detection of other tumor types, such as gastrointestinal, colorectal and cervical cancers."

Reference: I. Sokolov el al., "Noninvasive diagnostic imaging using machine learning analysis of nanoresolution images of cell surfaces: Detection of bladder cancer," PNAS (2018). www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1816459115