Source: Multiple Jul 11, 2018 7 years, 6 months, 2 weeks, 6 days, 14 hours, 6 minutes ago

A new approach established at the University of Zurich sheds light on the effects of anti-cancer drugs and the defense mechanisms of cancer cells. The method makes it possible to quickly test various drugs and treatment combinations at the cellular level.

Cancer cells are cells over which the human body has lost control. The fact that they are transformed body cells makes it all the more difficult to combat them effectively—whatever harms them usually also harms the healthy cells in the body. This is why it is important to find out about the

cancer cells' particular weaknesses.

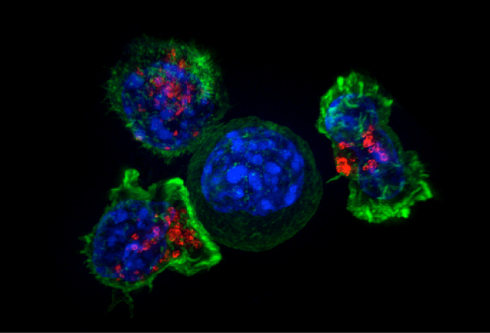

Killer T cells surround a cancer cell. Credit: NIH

In certain types of breast and ovarian

cancer, for example, such weakness is caused by mutations in genes that play a role in DNA repair. Treating cancer cells of this kind with a group of newly approved PARP inhibitors makes it difficult for these cells to replicate their DNA, and they ultimately perish. Normal cells, however, can solve such problems using their intact DNA repair machinery.

Effect of drugs observed in thousands of cells

The Department of Molecular Mechanisms of Disease of the University of Zurich uses cancer cell cultures to investigate the exact effects of this new group of drugs. "Our method of fluorescence-based high-throughput microscopy allows us to observe precisely when and how a

drug works in thousands of cells at the same time," explains postdoc researcher Jone Michelena.

Her measurements have revealed how PARP inhibitors lock their target protein in an inactive state on the cells' DNA and how this complicates DNA replication, which in turn leads to DNA damage. If this damage is not repaired quickly, the cells can no longer replicate and eventually die.

The new approach enables researchers to analyze the initial

reaction of cancer cells to PARP inhibitors with great precision. What's special about the very sensitive procedure is the high number of individual cells that can be analyzed concurrently with high resolution using the automated microscopes at the Center for Microscopy and Image Analysis of UZH. Cancer cells vary and thus react differently to drugs depending on their mutations and the cell cycle phase they are in. The UZH researchers have now found a way to make these differences visible and quantify them precisely.

Rapid and precise testing of cancer cells

Outside of the laboratory, the success of PARP inhibitors and other cancer medication is complicated by the fact that in some patients the cancer returns—after a certain point, the cancer

cells become resistant and no longer respond to the drugs. The high-throughput method employed by UZH researchers is particularly useful for this kind of problem: Cells can be tested in multiple conditions with short turnover times, and specific genes can be eliminated one by one in a targeted manner. Doing so can reveal which c

ell functions are needed for a certain

drug to take effect.

In addition, mechanisms of drug combinations can be analyzed in great detail. In her study, Jone Michelena has already identified such a combination, which inhibits cancer cell proliferation to a significantly higher extent than the combination's individual components by themselves. "We hope that our approach will make the search for strategies to combat cancer even more efficient," says Matthias Altmeyer, head of the research group at the Department of Molecular Mechanisms of Disease at UZH.

Reference: Jone Michelena et al, Analysis of PARP inhibitor toxicity by multidimensional fluorescence microscopy reveals mechanisms of sensitivity and resistance, Nature Communications (2018). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-018-05031-9