Researchers Discover Ways To Deal With HIV Reservoirs To Create Longer Periods Of Virus Suppression And Possible Cure

Source: Thailand Medical News Oct 23, 2019 5 years, 5 months, 1 week, 4 days, 1 hour, 17 minutes ago

An new research study involving an international collaboration that included the University of Cape Town (UCT), Centre for the AIDS Program of Research in South Africa (CAPRISA) and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC) has revealed an unexpected finding that could lead to better therapies towards reducing the HIV reservoir, a major barrier to developing a cure for

HIV. The reservoir consists of viral DNA that survives hidden in the body even after indefinite treatment with

antiretrovirals.

Antiretroviral treatment can suppress

HIV, but it cannot cure the infection.

Commonly available

antiretroviral treatments stop progression of the disease, and in most cases, prevent individuals from developing the immune deficiency syndrome AIDS. These

antiretrovirals can reduce a person’s viral load to the point where it’s undetectable with standard tests.

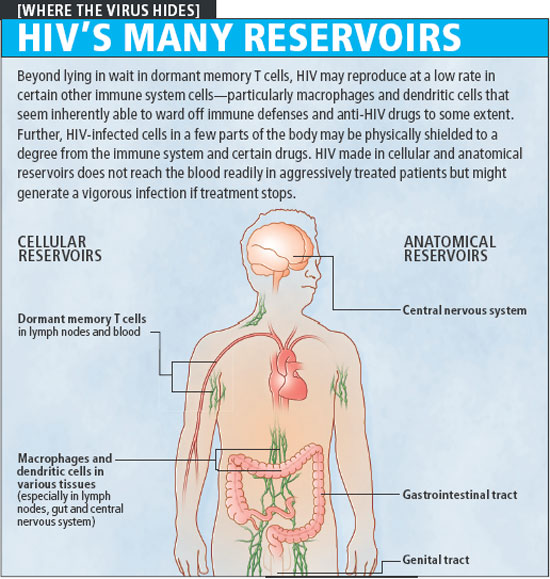

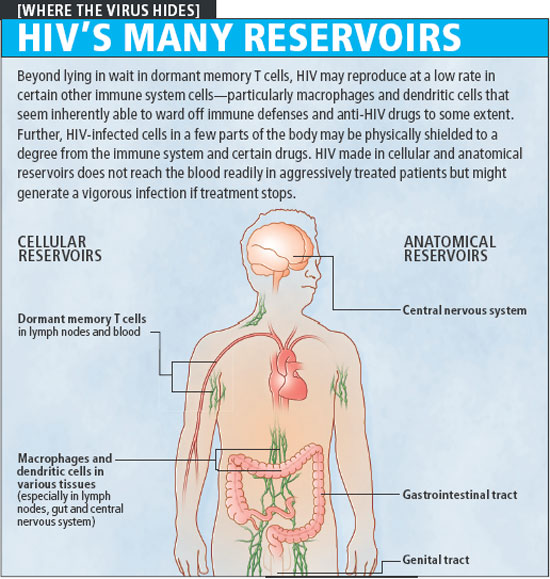

But current antiretroviral treatments cannot completely eradicate the virus, which persists in long-lived reservoirs in the DNA of immune cells.

HIV encodes itself in the DNA of millions of CD4 immune cells, just waiting for the opportunity to replicate should antiretroviral treatment ever stop.

The complex dynamics of how this reservoir forms, though, have been largely unknown. Scientists had thought that it formed continuously during infection prior to treatment.

Now researchers have genetic evidence that this is not the case, and that initiation of

antiretroviral treatment could be altering the biology of the human immune system in such a way that it allows the

HIV reservoir to form or stabilise.

UCT’s Professor Carolyn Williamson, the head of the Division of Medical Virology, who led the study with Professor Ron Swanstrom of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC) commented in a phone interview with

Thailand Medical News, “We hope reducing the size of the

HIV reservoir will take us a step towards achieving our goal o

f enabling people to stop treatment without the virus rebounding.”

Since

HIV reservoirs can persist for many decades, patients are required to stay on treatment for the rest of their lives. Thus, this reservoir is a fundamental obstacle to a cure. But without an understanding of how it forms, there is little chance of ever eradicating it.

By using blood samples collected from nine South African women from the CAPRISA 002 cohort in Durban, the research team embarked on a study to understand the timing the formation of the

HIV reservoir.

The

HIV virus evolves very rapidly: it’s one of the fastest evolving entities known. Not only does it reproduce quickly in a person, the virus can produce billions of copies a day, but its genetic copying is sloppy, introducing mutations as it goes. But this characteristic of

HIV also offers a tool for researchers to map a timeline of the virus’s evolution.

Comparing the genetic sequence of the virus in the women’s latent

HIV reservoir with the sequence of the active viruses circulating in their blood in the years leading up to the start of treatment, the researchers could get an indication of when the reservoir formed.

If the viral sequences from the

HIV reservoir were closely related to that of the viruses in the bloodstream around the time treatment started, it would indicate the reservoir had formed then. Whereas if the reservoir sequences were similar to viruses circulating during early infection and before treatment, it would suggest that it was formed continuously throughout infection.

Lead author of the study, Dr Melissa-Rose Abrahams from the UCT Division of Medical Virology commented “Surprisingly, we found that the majority of the viruses in the

HIV reservoir of these women, about 71% most closely resembled viruses circulating within a year of therapy starting. This is a much higher than you’d see if the reservoir formed continuously before treatment.”

This suggests that immune cells infected with the virus at the time treatment begins transition into a silent state and seed the reservoir. In Africa, most people initiate therapy during chronic infection. Eliminating the

HIV reservoir in these individuals was considered particularly difficult due to the widely held belief that the reservoir formed continuously prior to starting therapy.

The unexpected finding that much of the reservoir originates around the time of therapy initiation provides hope that one can restrict

HIV reservoir formation in these patients. This finding points to an opportunity for intervention.

If researchers can come up with a biological intervention to reduce the number of infected cells transitioning to latency at the time of initiating treatment, it’s possible they could restrict the establishment of most of this viral reservoir. The researchers are now exploring the idea that the initiation of antiretroviral treatment dampens the human immune system by reducing the presence of active

HIV. This makes the immune cells where the virus is embedded more likely to turn into long-lived memory cells that may ultimately constitute much of the long-term viral reservoir.

The results of these findings will enable medical researchers to develop treatment protocols that can help suppress the

HIV viruses longer or maybe even eradicate

HIV completely one day.

Reference: Abrahams M et al. (2019) The replication-competent HIV-1 latent reservoir is primarily established near the time of therapy initiation. Science Translational Medicine 11(513): eaaw5589. DOI: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaw5589