University of Maryland study finds that bacteria can form clumps in pleural fluid of the lungs

Nikhil Prasad Fact checked by:Thailand Medical News Team Jul 24, 2024 1 year, 5 months, 1 week, 19 hours, 34 minutes ago

Medical News: A groundbreaking study from the University of Maryland School of Medicine-USA has revealed fascinating insights into how bacteria behave in the pleural fluid, the fluid surrounding the lungs. This discovery could revolutionize the treatment of thoracic empyema, a severe lung infection. This

Medical News report delves into the study's findings and their implications for medical practice.

University of Maryland study finds that bacteria can form clumps in pleural

University of Maryland study finds that bacteria can form clumps in pleural

fluid of the lungs

The Hidden World of Bacterial Clumps

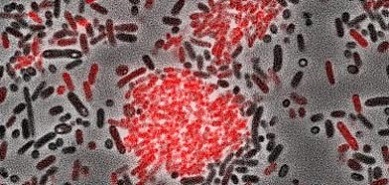

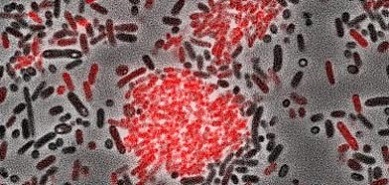

For the first time, researchers have shown that bacteria can form aggregates, or clumps, in pleural fluid, similar to how they behave in joint fluid. This study, led by Dr James B. Doub and Dr Nicole Putnam from the University of Maryland, explored how these bacterial clumps can resist antibiotics, making infections harder to treat.

"We know that bacteria in joint fluid form protective aggregates, but it wasn't clear if the same thing happened in other body fluids," said Doub. "Our study shows that bacterial aggregation is not just a phenomenon in joint infections but also occurs in the pleural space."

Understanding the Study

To understand how bacteria aggregate in pleural fluid, the researchers used common bacteria known to cause thoracic empyema: Streptococcus mitis, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. They tested these bacteria in different types of pleural fluid under various conditions.

Methods and Conditions:

-Three types of pleural fluid: transudative (normal), low-protein exudative, and high-protein exudative.

-Bacteria were grown in these fluids under static conditions and two dynamic conditions (30 RPM and 120 RPM shaking).

-Using these methods, they observed that bacterial clumping occurred under high-speed shaking in all pleural fluid types but not in static conditions or low-speed shaking in less protein-rich fluids.

Key Findings: Bacterial Clumping and Resistance

The study found that:

-High-speed shaking promotes aggregation: All bacterial types formed clumps under high-speed shaking conditions (120 RPM), mimicking the dynamic conditions in the body.

-Protein-rich fluids foster clumping: Under low-speed shaking (30 RPM), only the high-protein exudative fluid supported bacterial aggregation.

-Resistance to antibiotics: Bacterial aggregates showed significant resistance to antibiotics, which could explain why thoracic empyema is challenging to treat with antibiotics alone.

The Role of Tissue Plasminogen Activator (TPA)

A crucial part of the study was testing if tissue plasminogen activ

ator (TPA), a drug that breaks down blood clots, could disperse these bacterial clumps. TPA successfully dispersed the aggregates, making the bacteria more susceptible to antibiotics. However, TPA alone did not kill the bacteria.

Implications for Treatment

The study suggests that using TPA in combination with antibiotics could significantly improve the treatment of thoracic empyema. This approach helps dissolve the bacterial clumps, allowing antibiotics to reach and kill the bacteria more effectively.

"This study provides a pathophysiological underpinning for why antibiotics alone have limited utility in treating empyema," said Doub. "Combining antibiotics with agents like TPA could enhance treatment outcomes."

Why This Matters

Thoracic empyema is a serious condition that often requires invasive procedures like chest tube drainage and surgery. Understanding how bacteria aggregate in pleural fluid can lead to less invasive, more effective treatments.

Study Limitations and Future Research

While the findings are promising, the study has limitations:

-Limited bacterial species: Only four common bacteria were tested. Future research should explore other bacteria that cause thoracic empyema.

-Assumed conditions: The study assumed the in vivo (within the body) movement of pleural fluid mimics the conditions tested in the lab. More research is needed to confirm this.

-Mechanistic understanding: The study did not fully explore why bacterial aggregates are resistant to antibiotics or how TPA enhances antibiotic effectiveness.

Future research should address these limitations and further investigate the mechanisms behind bacterial aggregation and resistance.

Conclusion

This study marks a significant step forward in understanding bacterial behavior in pleural fluid and opens the door to new treatment strategies for thoracic empyema. By combining antibiotics with TPA, doctors may be able to more effectively treat this challenging condition, reducing the need for invasive procedures and improving patient outcomes.

The study findings were published in the peer-reviewed journal Infectious Disease Reports.

https://www.mdpi.com/2036-7449/16/4/46

For the latest medical research breakthroughs, keep on logging to Thailand

Medical News.

Read Also:

https://www.thailandmedical.news/news/japanese-researchers-warn-that-covid-19-infections-can-give-rise-to-systemic-capillary-leak-syndrome-scls,-also-known-as-clarkson-s-disease

https://www.thailandmedical.news/news/university-of-north-carolina-murine-study-shows-that-sars-cov-2-infections-ultimately-lead-to-chronic-pulmonary-epithelial-and-immune-cell-dysfunction